How a People Reimagined God, Worship, and Themselves

Between 1200–500 BCE, the people we later call “Jews” underwent one of the most profound religious transformations in history. What began as Canaanite polytheism evolved — slowly, often painfully — into the exclusive monotheism of Judaism. This transition wasn’t instantaneous and didn’t begin in opposition to Canaanite culture. Instead, the Israelites emerged from within it, sharing language, deities, and rituals with their neighbors. The real rupture came not with conquest, but with crisis — and especially with the Babylonian Exile.

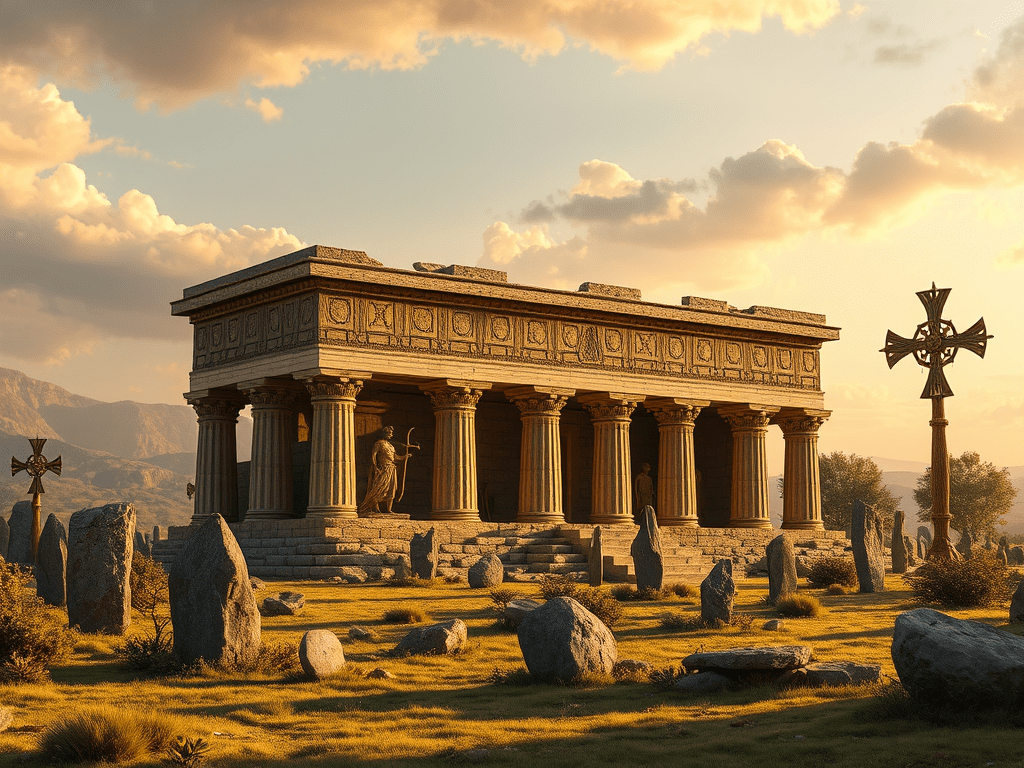

1. The Religion Before Judaism: Canaanite Polytheism

Before “Judaism” existed, the people of ancient Israel and Judah practiced a religion much like that of other Canaanite city-states. It was polytheistic, localized, and deeply tied to the land and cycles of fertility.

- Gods of the Canaanite Pantheon:

- El – the supreme god, ruler of the divine assembly.

- Baal – storm and fertility god, worshipped widely.

- Asherah – a mother goddess, possibly seen as Yahweh’s consort in early Israelite religion.

- Anat, Astarte, Resheph, and others.

- Ritual Practices:

- Sacrifices, libations, and sacred feasts.

- Cult objects like standing stones (masseboth) and Asherah poles.

- Worship took place at high places, local shrines, and eventually in temples.

Israelite religion was not originally monotheistic. It was henotheistic — Yahweh was their god, but not yet the only god.

2. The Rise of Yahweh and the Seeds of Monotheism

- Yahweh likely entered the Israelite pantheon from the southern regions (Edom, Seir, Midian) (cf. Deut 33:2; Judges 5:4).

- For centuries, Yahweh coexisted with other gods. Archaeological finds like the 8th-century BCE inscriptions at Kuntillet Ajrud speak of “Yahweh and his Asherah.”

- The push toward exclusive Yahweh worship came through prophets and political reformers:

- Prophets like Elijah, Hosea, and Isaiah challenged Baal worship.

- Kings like Hezekiah and Josiah tried to centralize worship in Jerusalem and purify it of other deities.

Still, these reforms were partial and short-lived. Most Israelites likely practiced a syncretic form of religion into the 7th century BCE.

3. The Babylonian Exile (586–539 BCE): A Theological Crisis

The Babylonian Exile was the turning point. Judah rebelled against Babylonian control; in retaliation, Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Jerusalem, razed the Temple, and deported much of the elite population to Babylon.

This catastrophe forced a complete religious rethinking:

3.1. Where Is God Without the Temple?

- The Temple in Jerusalem had been the only legitimate place of worship since Deuteronomic reform.

- Its destruction created a crisis: Had Yahweh been defeated? Was the covenant broken?

- The answer developed in exile: Yahweh had not lost; he had punished his people for their sins (Jer 25:8–11; Lam 1).

3.2. Birth of a Text-Based Religion

- Without a temple, religion shifted to law, prayer, fasting, and community observance.

- Scribes and priests compiled and edited Israel’s traditions — including much of the Pentateuch.

- Torah became the portable homeland of the exiled people.

3.3. A Universal God Emerges

- In exile, particularly in the writings of Second Isaiah (Isaiah 40–55), Yahweh is no longer just Israel’s god — he is the only god who exists: “I am the LORD, and there is no other; besides me there is no god.” (Isaiah 45:5, NRSV)

This is the true birth of monotheism.

4. Return and Reinvention (Post-539 BCE)

When Cyrus of Persia conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, he allowed exiles to return. But only some did.

- Those who returned rebuilt the Second Temple (completed 515 BCE), but this temple never regained its former spiritual centrality.

- Under Ezra and Nehemiah, the returned elite emphasized:

- Strict observance of the Torah.

- Ethnic and religious purity (e.g., bans on intermarriage).

- Exclusive loyalty to Yahweh — no syncretism.

This is when Judaism as a distinct, text-based, monotheistic religion takes shape.

5. Summary: How Judaism Emerged

| Canaanite Israelite Religion (pre-586 BCE) | Judaism (post-539 BCE) |

|---|---|

| Polytheistic or henotheistic | Monotheistic |

| Land-based, temple-centered | Diaspora-capable, Torah-centered |

| Cult of Yahweh alongside other gods | Exclusive worship of Yahweh |

| Oral traditions and local shrines | Codified scripture and law |

| Kingship as central | Torah and community elders as leaders |

Final Thought:

Judaism did not begin with Abraham or Moses in any historical sense — it began in Babylon, amid despair and displacement. Stripped of their land, temple, and king, the Judean exiles asked: What does it mean to be God’s people now? The answer — grounded in monotheism, scripture, and law — became the foundation of Judaism.

A Note From Me…

I’m not a scholar — I’m just someone trying to understand the Bible from the ground up. What I’ve shared here is based on what historians and archaeologists have found so far. I might not have it all exactly right — but I’m learning, and I’m sharing what I learn as I go

Excellent idea. Providing sources not only supports your content’s credibility but also helps readers deepen their own understanding. Here’s a curated list of academic, archaeological, and textual sources for fact-checking and further reading, divided by type.

Common Sources & Further Reading

Primary Textual Sources (Ancient Texts)

These are ancient documents or inscriptions that scholars rely on to reconstruct the religious and cultural landscape of ancient Israel and its neighbors.

- The Hebrew Bible (NRSV preferred for study)

- Especially: Deuteronomy, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Ezra–Nehemiah

- Ugaritic Texts (Ras Shamra Tablets)

- Found in modern Syria, these 14th–13th century BCE texts reveal Canaanite religion and myth (esp. Baal Cycle).

- The Merneptah Stele (ca. 1208 BCE)

- Egyptian inscription mentioning “Israel” in Canaan — earliest external reference to Israelites.

- Kuntillet Ajrud Inscriptions (8th century BCE)

- Mention “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” — evidence of early syncretism.

- The Cyrus Cylinder (539 BCE)

- Persian decree permitting exiles to return; confirms biblical account in Ezra 1.

- Lachish Letters (6th century BCE)

- Hebrew inscriptions from Judah just before Babylonian conquest — snapshots of military and religious anxiety.

Secondary Scholarly Sources (Modern Academic Works)

These provide historical-critical perspectives and archaeological interpretations of Israelite religion and the development of Judaism.

1. Books for General Readers and Advanced Beginners

- Mark S. Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (Eerdmans, 2002)

- Seminal book on how Yahweh emerged from a larger pantheon.

- Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? (HarperOne, 1997)

- A well-known introduction to the sources behind the Pentateuch.

- Israel Finkelstein & Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2001)

- Integrates archaeology and biblical history, especially regarding the monarchy and exile.

- Michael Coogan, A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament (Oxford University Press, latest ed.)

- Balanced textbook for students and curious readers.

- John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (Sheffield Academic Press, 2000)

- Academic but readable, on Canaanite religion and its Israelite transformation.

2. Books for In-Depth Study

- Karel van der Toorn, Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible (Harvard, 2007)

- Explores how written scripture developed in the Exile and afterward.

- Jon D. Levenson, Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought of the Sixth Century BCE (Yale, 1978)

- Deep dive into theology of the Exilic period.

- Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Harvard, 1973)

- Classic in understanding the shift from mythic polytheism to Israelite monotheism.

Archaeological Resources

- Biblical Archaeology Review (Magazine/Journal)

- Popular-level summaries of cutting-edge discoveries.

- The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA)

- Official repository of archaeological finds in Israel.

- Excavation Reports from:

- Hazor, Megiddo, Lachish, Jerusalem, Khirbet Qeiyafa

Online Resources (Credible Academic Tools)

- Oxford Biblical Studies Online (subscription-based)

- The BAS Library (Biblical Archaeology Society)

- The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls (hosted by the Israel Museum)

- SBL (Society of Biblical Literature) – open access articles and book chapters

- Livius.org – historical articles on ancient Near Eastern peoples

Suggested Reading Plan for New Learners:

- Start with The Bible Unearthed (Finkelstein & Silberman) — readable, engaging.

- Then go to The Early History of God (Smith) for theological development.

- Use Who Wrote the Bible? (Friedman) to understand textual development.

- Supplement with reading biblical texts — especially Isaiah 40–55, Deuteronomy, and Ezra–Nehemiah — using the NRSV.

Leave a comment