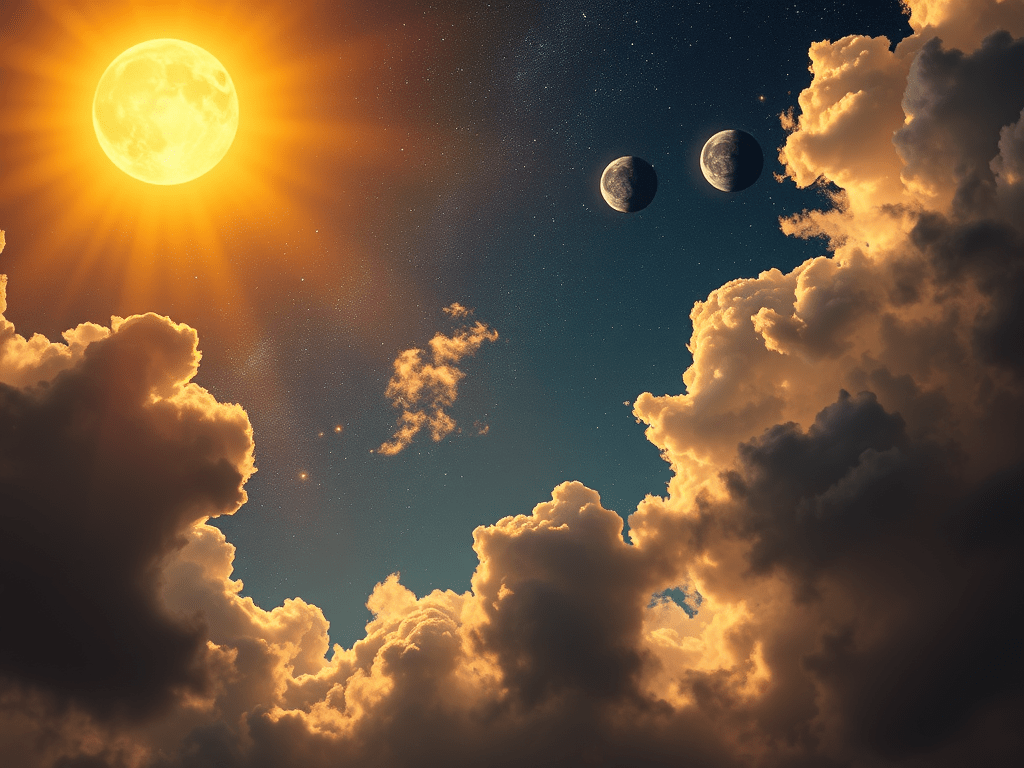

And God said, “Let there be lights in the vault of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark sacred times, and days and years, and let them be lights in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth.” And it was so. God made two great lights—the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars. God set them in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth, to govern the day and the night, and to separate light from darkness. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the fourth day.

(Genesis 1:14–19, NIV)

Summary

On the fourth day of creation, the text describes the creation of the sun, the moon, and the stars—referred to not by name, but as “lights” placed in the “vault of the sky.” These lights serve multiple purposes: to provide illumination, to distinguish day from night, and to function as markers for “sacred times,” days, and years. The day ends with the familiar refrain: “And there was evening, and there was morning—the fourth day.”

Historical & Cultural Background

This section of Genesis reflects ancient Near Eastern cosmology, where the sky was imagined as a solid dome (“vault”) separating the heavens from the earth. The description aligns with a flat-earth model where the stars, sun, and moon are embedded or placed into this dome.

Importantly, the Hebrew Bible avoids naming the sun (shemesh) and moon (yareach) here—words commonly associated with deities in neighboring cultures (e.g., Shamash and Yarikh). Instead, they’re called “greater light” and “lesser light.” This may be an intentional move to demythologize these celestial bodies. In the Ancient Near East, the sun and moon were worshipped as divine beings. Here, they are created objects, functional rather than divine. This text subtly asserts that the God of Israel is distinct and above these objects of worship.

The phrase “to mark sacred times” is a reference to the calendar-based festivals and rhythms of religious life. In early Israelite religion (and in many ancient societies), timekeeping was tied directly to the positions of celestial bodies. This framework for structuring time precedes any priestly system, suggesting that awareness of sacred timing was rooted in cosmic observation.

Hebrew Language & Word Notes

- “Lights” (ma’orot) – This term means luminaries or light-bearers. It’s used here in plural and avoids divine connotation.

- “Vault” (raqia) – From the root raqa, meaning “to spread out” or “to hammer out.” It suggests something firm and solid—an idea common in ancient cosmology.

- “Signs” (otot) – Often means omens, symbols, or divine indicators. These could be astrological signs or seasonal markers, depending on context.

- “Sacred times” (moedim) – A loaded term. It’s the same word used later for the festivals in Leviticus (like Passover and Sukkot). This implies an early awareness of cyclical sacred observances tied to the cosmos.

Major Themes & Questions

- Demotion of celestial bodies: In contrast to other ancient myths (like in Mesopotamia or Egypt), Genesis 1 does not deify the sun or moon. They’re functional, not worshipped. This quiet polemic reflects a theological shift from polytheism to monolatry or monotheism.

- Cosmic calendar: Time itself is being structured. The ordering of days and sacred times based on celestial bodies reflects a desire for rhythm and regularity. It also hints that sacredness is embedded in nature’s cycles.

- Day Four paradox: If light was created on Day One, why are the sun, moon, and stars created only on Day Four? This raises interpretive questions. Is this text structured thematically (not sequentially)? Is light in Day One symbolic or theological? Ancient readers may not have asked this in a scientific way, but it’s an important observation for modern readers.

Related Posts

Further Reading

- Walton, John H. The Lost World of Genesis One

- Day, John. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea

- Heiser, Michael. The Unseen Realm

- Frankfort, Henri. The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man

Disclaimer & Call to Action

This post approaches the biblical text from a non-Christian, scholarly lens. The goal is not to promote or undermine faith, but to encourage thoughtful, well-informed engagement with the text.

If you’re enjoying this journey through Genesis, consider subscribing or sharing with someone who might also want to explore sacred texts from a historical and literary point of view.

Leave a comment